Holy Cross Roads

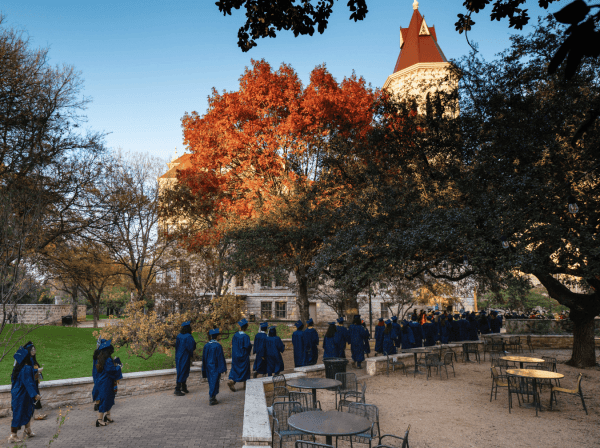

Between 1946 and 1984, a fledgling St. Edward’s University faced serious challenges. Against tremendous odds, four humble and faithful Holy Cross Brothers, each called to serve as president, brought the university back from the brink and sustained St. Edward’s through financial, organizational and cultural transition.

On a blistering hot day in July 1946, Brothers Edmund Hunt, CSC, and Simon Scribner, CSC, stepped off the train that had carried them from Chicago to St. Louis to Austin. Waves of heat rose from the pavement, and the men’s black suits absorbed them all. When they reached the St. Edward’s campus, the hilltop felt deserted. Most of the university students had left to join the service during World War II, which had ended a year earlier. Main Building and Holy Cross Hall were overdue for repairs. The grass was hip high — and probably full of rattlesnakes — and cicadas mocked them from the branches of the trees. “Well, here we are,” the duo thought. “What have we gotten ourselves into?”

Hunt and Scribner’s arrival in Austin marked the beginning of a new era at St. Edward’s. The previous year, the priests and brothers of the Congregation of Holy Cross had voted to split into separate societies. The brothers were given responsibility for St. Edward’s University, an institution that had barely survived the Depression, only to be drained by the war. The task facing Hunt, the first brother-president of St. Edward’s, and Scribner, the vice president, was daunting. But they, along with Holy Cross Brothers who were already working in Austin and the leaders who followed them, would meet the challenge with the clear-eyed pragmatism and humility that are hallmarks of the congregation.

Top Left: Brother Edmund Hunt, CSC, President, 1946–1952; Top Right: Brother Elmo Bransby, CSC

President, 1952–1957; Bottom Left: Brother Raymond Fleck, CSC, President, 1957–1969; Bottom Right: Brother Raymond Fleck, CSC, President, 1957–1969

The only four brother-presidents in St. Edward’s history — Edmund Hunt, Elmo Bransby, Raymond Fleck and Stephen Walsh — led the university through a 38-year period when it sometimes appeared that St. Edward’s would not survive. These decades were filled with challenges for colleges, especially Catholic ones, across the country, as both higher education and the church underwent dramatic changes. The brother-presidents marshaled their limited resources and made strategic, if difficult, decisions to help St. Edward’s weather the transitions and enter the 20th century with a foundation of excellence. While they quietly worked to transform a university, they lived the mission of the Brothers of St. Joseph, the religious community founded by Father Jacques Dujarié that would become the Congregation of Holy Cross.

“These are the guys who made St. Edward’s,” says Brother Richard Daly, CSC, ’61, who knew all four of the brother-presidents. “They created something out of nothing in the beginning.”

1820 - Father Jacques Dujarié starts the Brothers of St. Joseph in France

1837-The Congregation of Holy Cross forms when the Brothers of St. Joseph merge with the Auxiliary Priests

1872-Mary Doyle bequeaths a 400-acre farm to the Catholic Church in Austin for an educational institution

1878 -The first students attend St. Edward’s Academy, which Father Edward Sorin established on Doyle's land

Arrival

In the hot summer of 1946, Hunt and Scribner started preparing the empty campus for the influx of student-veterans they knew would soon arrive, supported by the GI Bill. The university had no money for facilities, so Hunt borrowed enough to purchase war-surplus buildings from Camp Swift, an Army training camp near Bastrop, and have them shipped at night, in pieces, to campus. Old barracks, which Scribner described as being “held together with tacks and chewing gum,” served as student residences, classrooms and the original St. Joseph Hall. The brothers converted the rifle range that, before the war, had been a theater — and before that, a machine shop — into Our Lady of Victory Chapel. Hunt built the pews himself.

As students arrived and the campus returned to life, Hunt and Scribner reorganized the academic curriculum and created a night-school program to accommodate students from Bergstrom and Gary Air Force Bases. Hunt, 36, had earned his doctorate at the University of Chicago and had taught classical languages and history at the University of Notre Dame before being dispatched to Texas. At St. Edward’s, he taught courses in languages, history and art history and led “Great Books” discussions with Scribner, all while serving as president.

A handsome man who somehow always had a tan, Hunt was known among students — behind his back — as “the Greek god.” He often wore a cape. Yet he also enjoyed manual labor. Colleagues reported that he would finish teaching a class and immediately set to laying linoleum, pouring concrete sidewalks, repairing a roof or painting walls.

“Edmund Hunt cannot be underestimated in terms of getting St. Ed’s off the ground following World War II,” says Daly, who has researched the brother-presidents and who took history courses from Hunt in the 1950s. “He made do with nothing.”

Hunt, though, wasn’t satisfied with nothing. By 1949, he was writing letters to prominent Texas philanthropists — Amon Carter, Herman Brown, Jesse Jones — asking for their support. St. Edward’s was then at capacity with 300 students and could accept no more until it built another college dormitory. The school had no endowment and practically no money for scholarships. It owed money for the barracks buildings. And it really needed a gymnasium. Could they help?

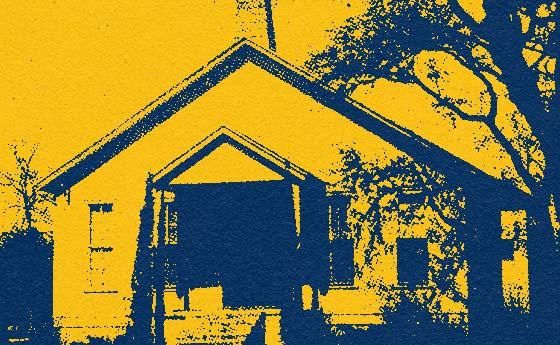

Top Illustration: Prior to becoming the chapel in 1949, the building was a theater, a machine shop and a rifle range.

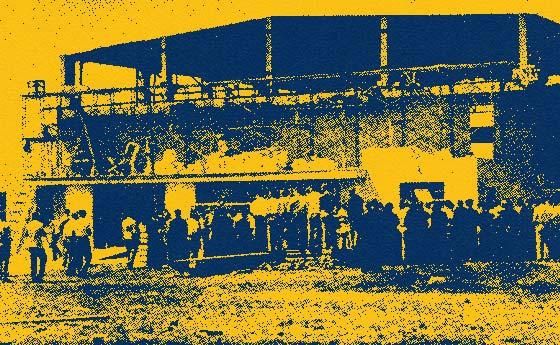

Middle Illustration: The construction of the gymnasium (now UFCU Alumni Gym) in 1950 relied on donated materials and free labor.

Bottom Illustration: Brother Edmund Hunt, CSC, oversaw the construction of the gymnasium. He built the original bleachers himself and later refinished the floor.

Hunt pulled together enough money, donated materials and free labor to build a gymnasium, today’s UFCU Alumni Gym, in 1950. (Hunt constructed the original bleachers himself.) A decade later, after his term as president had ended and he’d spent time in Europe and back at Notre Dame, he returned to St. Edward’s to lead the Division of Humanities. He dedicated his summers to refinishing the gym floor in the airless, stifling building, pressing a brother or a student like Daly into service alongside him.

Hunt exemplified what Associate Director of Transfer Student Services Michael Kinsey ’85 calls the “unstated charisms” of Holy Cross. “The well-known characteristics of Holy Cross are in the St. Edward’s mission statement: the courage to take risks, an international perspective, meeting students where they are,” Kinsey says. “But there are other less public characteristics, things like, ‘If there’s something that needs to be done, you just do it.’ So, if you’re the president of the university and the floor needs to be tiled, you just get down there with the grout and you tile it. You don’t say, ‘That’s not my job.’ You work hard, and you do whatever needs to be done and whatever the situation calls for.”

The original André Hall, pictured here in 1950, was a reassembled barracks building from Camp Swift, an Army training camp near Bastrop. André Hall was initially located by the gymnasium, then moved near the current St. André Apartments, where it became the south wing of Vincent Hall. During a move, the old barracks got stuck and Vincent Hall sat in the middle of center field of the baseball diamond. Any ball that hit the building was an automatic double.

In those days, the Congregation’s rules limited the term of a St. Edward’s University president to six years. So in the summer of 1952, Hunt passed the torch to Brother Elmo Bransby, CSC, an educational psychologist who had joined the St. Edward’s faculty two years earlier and directed the scholasticate, the student brothers’ residence. Bransby tackled a problem that had come into focus during Hunt’s tenure: The university was not regionally accredited, a deficiency that was costing it grants as well as students. Bransby applied for accreditation by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, the same body that accredits St. Edward’s today. You’ll need a library, a science building and a real dormitory, the association responded. So Bransby oversaw the construction of the first library, which opened in 1954, and commissioned a master plan for the western portion of campus.

The terrible Texas drought of the 1950s had ended the university’s farming operation on part of the original Doyle farm, and during Bransby’s tenure the university sold land to make way for Interstate 35, Woodward Street and Ben White Boulevard. The proceeds helped pay for new buildings: student residence André Hall, and a science building designed with help from Brother Romard Barthel, CSC, in physics (who also directed the choir) and then-Brother Raymond Fleck, CSC, a young chemistry professor. In 1957, when Bransby was assigned to the Eastern Vice Province, Fleck was named the next president of St. Edward’s.

1925 - St. Edward’s receives its state charter as a university

1945 - The Congregation of Holy Cross establishes separate provinces for its priests and brothers

1946 - The Brothers of Holy Cross assume responsibility for St. Edward's

1946 - Brother Edmund Hunt, CSC, becomes the first brother-president

Expansion and Upheaval

Fleck built on the foundation Bransby had laid: He completed the accreditation process and built the facilities in Bransby’s master plan, a task that required still more fundraising. He also led the university as the country began to experience a series of dramatic changes in higher education, social norms and the Catholic church, all of which would influence the future of St. Edward’s.

“I don’t say this as a put-down, but Edmund [Hunt] and Elmo [Bransby] kind of ran the place by the seat of their pants,” says Fleck, 93, who today lives in Southern California. He remembers the university treasurer’s surprise when he asked for a copy of the budget early in his presidency; evidently no one had been very interested in it before. Fleck and his team put together a 20-page document that spelled out how the university was organized and how it should operate.

In the late 1950s, when Fleck began his presidency, the brothers taught multiple classes and lived in the student residences as hall directors. They traveled across the country to recruit students, and some coached sports or managed the physical plant. “Everybody had two jobs,” Daly says. “Some people had three. These guys in the ’50s, ’60s and ’70s — they did it all. They had to.”

But Fleck could see that this system of staffing the university was not adequate for the long term. The brothers had academic expertise and were willing to work hard, but very few had training in college administration. In the late 1950s, higher education was professionalizing other areas of administration besides the historic role of academic affairs. St. Edward’s, Fleck realized, would need directors of student affairs, public relations, fundraising and finances.

His first step: Connect with Austin. “When I became president in 1957, St. Edward’s was a mystery to the average Austinite,” Fleck wrote in an unpublished memoir. “Was St. Edward’s a high school or a college? Or was it, perhaps, a seminary?”

Fleck, with help from an alumnus, developed the university’s first advertising campaign that reintroduced St. Edward’s to the community. He served as a founding member, then president, of the South Austin Rotary Club, where he met prominent local businessmen with expertise the university needed. Several of Fleck’s colleagues from the business community joined alumni representatives on the university’s lay advisory board, an idea Bransby had implemented near the end of his presidency.

Fleck oversaw the completion of André Hall, the science building, Doyle Hall, the dining hall (today’s Fine Arts Center), St. Joseph Hall and Premont Hall. But he knew it would be impossible to borrow money for all this construction. Instead, he hired the university’s first development director and began paying personal visits to prospective donors himself. He met with members of the Moody family in Galveston, who contributed first to their namesake academic building and, later, after Fleck spent a morning sipping lemonade on the porch with Mary Moody Northen, to the theater. He drove to South Texas to call on the East family, who contributed a significant gift to build the residence hall that bears the family name.

Raymond Fleck, who became president of the university in 1957, invited the sisters of the Immaculate Heart of Mary from Michigan to initiate Maryhill College for Women on the university campus. The sisters’ arrival provided a way for Fleck to launch a coordinate women’s college and nudge the university toward coeducation.

Fleck realized that the university’s future required answers to three major questions: Would the high school continue on campus? Would the university offer any graduate programs? And would St. Edward’s admit women? All three decisions would have significant implications for the physical space. He asked the South-West Province provincial, Brother John Baptist Titzer, CSC, who provided answers: The high school would eventually leave the campus (it closed in 1967). The question of graduate programs could be answered later. And “the university” — which Fleck interpreted as himself — could decide about women students.

Fleck had watched Bransby float the idea of going coed and be met with immediate backlash. “I wasn’t going to walk the plank the way Elmo had,” he recalls, with a laugh. Instead, he suggested the university launch a coordinate women’s college on campus, an arrangement that existed at other colleges across the country. He figured that if the university could get an order of sisters to establish a women’s college that would operate parallel to the existing men’s institution, he could offer a compromise to suit both supporters and opponents of coeducation.

In 1966, members of the Immaculate Heart of Mary sisters arrived, at Fleck’s invitation, from Michigan to initiate Maryhill College for Women. Men continued their studies under the banner of Holy Cross College of St. Edward’s University. Soon, the impracticality of running two schools with duplicate staff on the same campus became clear. In 1969, Maryhill was dissolved and incorporated into a single coed St. Edward’s University of about 900 students. Fleck says he considers the admission of women one of his biggest accomplishments as president. “It was a pretty painful process for the university, but it has worked out just fine.”

1950 - The gym, a project of particular interest to Hunt, is built

1952 - Brother Elmo Bransby, CSC, becomes president

1954 - The university’s first library opens

1957 - Raymond Fleck (a Holy Cross Brother at the time) becomes the third brother-president

A Difficult Transition

A spirit of creativity and experimentation — and sometimes rebellion — permeated the country in the 1960s. Meanwhile, the Second Vatican Council of 1962–1965 dramatically reshaped Catholic life, including offering laypeople more significant roles in the church. Yet increased opportunities for the laity coincided with a drop in vocations; by 1970, the number of priests, brothers and sisters had begun to decrease.

For years, Catholic colleges had been able to lean on the labor of their religious, who worked without receiving salaries, to run the institutions. But as vocations declined, they could no longer rely on what Daly calls “a living endowment of inexpensive labor” to balance the budget.

Until the late 1960s, the lay advisory board had offered input, but all decisions about university governance were made by an all-Holy Cross board of trustees. As Fleck prepared to step down as president in 1969 and return to chemistry research (he would also leave the brothers, get married and have a family), he drafted a plan for the brothers to turn the operation and legal responsibility for the university over to a new governing board of trustees comprising members of the lay advisory board along with four brothers. Similar transitions were happening at Catholic colleges across the country.

Daly served on that first governing board and remembers that task as a challenging one. “None of us knew anything about being a trustee,” he recalls. “We needed some time to adjust to the reality of higher education.”

The president who succeeded Fleck was Edgar Roy, Jr., a layman with higher education experience, who began at St. Edward’s in the fall of 1969.

But Roy, while a kind person, was not the fundraiser that Fleck had been — and by those days, fundraising had become essential for university presidents. In the late 1960s the university had expanded enrollment and academic programs, but the lack of significant grants or private gifts during Roy’s tenure contributed to a large operating deficit. In January 1972, Roy resigned.

Dick Kinsey, who joined St. Edward’s in 1969 as Roy’s assistant and worked for the three following presidents, says the legal process of transferring the university to its new board took more than a year. The transition, which triggered people’s emotions about the larger changes in the church and culture, dominated Roy’s tenure as president.

“At this point in history, when all those Catholic institutions took the step toward the first lay president, that guy or gal generally failed,” Kinsey says. “[The brothers] were used to making university decisions sitting at the breakfast table. These people lived together and worked together and prayed together. Moving to a new operational model didn’t happen easily or well in some cases.”

1960 -The university’s first development director, T.A. Paulissen, is hired

1966 - Maryhill College for Women opens as a separate, “coordinate” institution on the St. Edward’s campus

1967 - St. Edward’s High School closes

1969 - Women are admitted to St. Edward’s for the first time and Maryhill College dissolves

Back from the Brink

The man chosen to right the ship was Brother Stephen Walsh, CSC, ’62, then the dean of Education. With his imposing stature and booming voice, Walsh could intimidate. “He wouldn’t tolerate much baloney,” Kinsey remembers. But he had a good sense of humor and the respect of the faculty.

“He had a clear picture of what an academic institution like St. Edward’s — a Catholic institution — ought to look like,” Kinsey says. “And he worked toward that, while at the same time appreciating the value of a quirky faculty and the need for there to be room for idiosyncrasies.”

The board appointed Walsh interim president in January 1972 and installed him as permanent president 11 months later. His initial task was to rescue the university from the brink of financial crisis. Walsh worked with Daly, his development director, to reestablish connections with prospective donors in the Austin business community.

But he still had to make cuts to balance the budget. The university was operating with a deficit that was approaching $700,000 by Walsh’s stint as interim president. In summer 1974, the Walsh-appointed Presidential Taskforce worked eight hours a day for seven weeks to revise the curriculum and recommend cuts to help the university live within its means. The group included Brother John Perron, CSC, who had started teaching English at St. Edward’s in 1970 and went on to direct the Freshman Studies and Writing programs.

“Those were desperate times,” says Perron, who now lives in the Brother Vincent Pieau Residence, the retirement facility next to campus. “The taskforce had to cut majors. It had to cut courses. It had to cut faculty in order to keep us afloat. There were some painful transitions.” But these efforts eliminated the deficit by the 1974–1975 school year.

Walsh understood that the university might be able to stabilize its enrollment — and enact its social justice mission — by serving students who fell outside the “traditional” college-going population. In 1972, he and Kinsey secured the first College Assistance Migrant Program grant, launching a program that endures to this day. In 1974, he initiated New College to serve adults who wanted to pursue a degree during evenings and weekends.

Walsh had a broader vision for the future of St. Edward’s that acknowledged significant changes like coeducation, the shift to lay leadership and the increasing diversity of the student body, says Brother John Paige, CSC, who served as dean of Education in the early 2000s.

“He wasn’t afraid to embrace those things,” Paige says. “Walsh was knowledgeable about them because he was an academic and an educator. He was able to move the university in a direction to turn over leadership to well-qualified lay folk who shared the same mission as Holy Cross and who brought skills and great diversity. So instead of a small mom-and-pop school on the hill, St. Edward’s University has progressed far beyond that in recent years.”

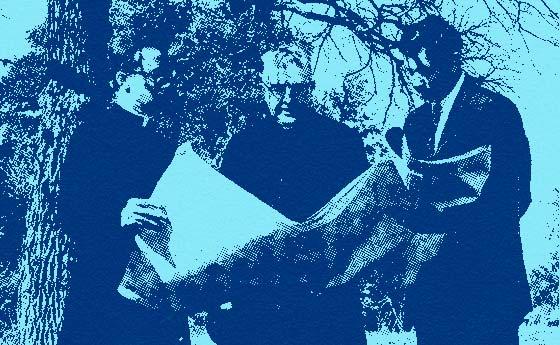

Brother Stephen Walsh, CSC, ’62 (center) assumed the helm at St. Edward’s in 1972 and brought a broad vision for the university’s future. Here, Walsh visits in front of Main Building with two students for an article that appeared in the Texas Star in 1973.

Walsh stepped down in May 1984 and took a sabbatical before working with Holy Cross high schools in Southern California and New Orleans. He returned to St. Edward’s in 2005 and served until his death in 2011 as the first executive director of the Holy Cross Institute. The brainchild of current St. Edward’s University President George E. Martin, the institute is designed to enhance Holy Cross education and equip laypeople to carry on the mission and charisms of the Holy Cross Congregation.

Today, the number of Catholic brothers in the United States is one-third what it was in 1970. The days of brother-presidents at St. Edward’s are long over. But the university has been forever shaped by the work of the four brother-presidents — Edmund Hunt, Elmo Bransby, Raymond Fleck and Stephen Walsh — who led it through the middle decades of the last century.

In 1949, Edmund Hunt wrote a fundraising letter to the Kenedy family — well-to-do ranchers in South Texas — laying bare his ambitions alongside the university’s struggles. “I hope eventually to make St. Edward’s the best Catholic college in the south, even though by my accomplishments so far, the hope seems dubious,” he wrote. “... We have about 300 college students because that is all the housing we have. ... By my check of the records, no person has ever given St. Edward’s more than $1,000 at any time. ...”

If Hunt were alive to see St. Edward’s today, it’s likely he would barely recognize it. Seven decades after he penned his request, enrollment has increased more than tenfold, the endowment surpasses $110 million, and St. Edward’s has been recognized as one of the nation’s best colleges — Catholic or otherwise. That success is the legacy of Hunt and the Holy Cross Brothers, who helped St. Edward’s flourish against overwhelming odds. It’s a legacy that’s carried forward in every student, professor or staff member, every proud alumnus, and all the lives that they touch.

1969 - Edgar Roy Jr., the university’s first lay president, is hired

1972 - Brother Stephen Walsh, CSC, ’62 is appointed president

1984 - Walsh, the last brother-president of St. Edward’s, steps down

2020 - The Holy Cross Brothers celebrate their 200th anniversary

Photo illustrations by Erin Strange