How to Draw Your Future at St. Edward's

Bright-yellow apricot flowers bloom on balconies. Eggs sizzle in the well-worn woks of bánh mì vendors dotting the sidewalk. Scooters zip between lines of cars packing the narrow roads. Always bustling and never quiet, Vietnam’s Ho Chi Minh City inundates the senses. Especially when you’re 3 years old, says Vy Nguyen ’20.

To keep her focused on childhood tasks — finishing breakfast, putting on her socks, reciting the alphabet — Nguyen’s mother and brother would draw for her. The simple pencil sketches of princesses and Japanese anime characters feature in her earliest memories. Eventually, she started drawing, too. She came to St. Edward’s University in 2015 as an international student and Art major. And last fall, that passion led her into Room 114 in the Fine Arts Center for Associate Professor of Art Alexandra Robinson’s Drawing Methods class.

After taking a foundation of drawing, visual studies and a clay class last year, Nguyen thought she knew what to expect — a focus on fundamentals, a deep dive into specific artists and mediums, and lots and lots of practicing traditional techniques. So she wasn’t quite prepared for Robinson’s pronouncement on the first day that the more uncomfortable students felt in class, the more successful they would be.

“Hearing that definitely made me uncomfortable,” Nguyen says with a laugh. A glance at the syllabus did, too — the final project would be a series of 20 drawings, each one created in no more than an hour. Throughout the semester, the students would also visit local studios, take a walking-drawing tour through their neighborhood while home for Thanksgiving break, and build simple drawing machines.

“I want to get students questioning and rethinking,” says Robinson, who has taught the class for seven years. Experience has helped her refine the projects so that each one is a perfect balance between stretching students’ brains and helping them gain confidence in their fledgling abilities. “They have already had technical drawing training, so how can they adapt that training to their own way of creating?” The end result is that students develop their own artistic process: no matter what they’re asked to do, they start to follow the same steps to develop their work. A growing familiarity with their own process helps them learn to trust their artistic instincts and embrace mistakes. It also makes the uncertainty of challenging assignments manageable, even exciting.

“I try to help students trust the process of drawing the thing, whatever it happens to be, and to find that ritualistic mental space where their work is made,” says Robinson. “I don’t provide answers, which are what students want at first.”

Graphic Design major Shelby Charette ’19 hurried across campus one balmy morning last October pondering that uncertainty. She knew something different would be happening in class that day, but Robinson had been intentionally vague, saying only that they would be experimenting with ways of making marks on paper. When she walked into the classroom, Charette immediately noticed something new: piles of sneakers, slippers and roller skates in the center of the room. Here we go, she thought.

First, Robinson asked the students to draw the shoes without looking at their papers. Then to draw with their nondominant hand. Then with their pencil in their mouths, and then with their toes. Charette didn’t hesitate. She slipped off her black Chuck Taylors, got on the floor and wedged her pencil between her toes. “I just went for it. Why not?” she remembers. “It opened my eyes to all the possibilities, all the different ways of expressing what I was seeing.”

Helping students find the courage to move toward the gray areas that dominate art, science, politics and society is the point of experiential learning, the education world’s term for learning by doing. “The idea is to make classroom learning come alive,” says Jennifer Jefferson, director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at St. Edward’s. “Bringing real-life situations into the classroom deepens students’ understanding of the interdisciplinary nature of life.”

While there are multiple definitions of experiential learning, Jefferson says, successful projects usually have three components: preparation, activity and reflection. Assigned readings or class discussions give students the background or context before they jump in to the experiential component. Afterward, the opportunity to reflect helps them assess how they did, what they learned, and in what ways the experience might be applicable to other areas of learning and life.

“It’s about looking at the world through the lens of the classroom and then bringing all those experiences back to campus to inform future learning,” says Jefferson. Students can adapt the knowledge and skills from one experience — how to problem-solve, how to collaborate, how to present, how to listen — to other experiences. Ultimately, she says, “students start to think about what they want their place in the world to be.”

Creating experiential projects and activities that cultivate that kind of intense self-discovery isn’t easy. “You start by asking ‘Where do I want my students to be at the end of this? All right, how do I get there?’” says Jefferson, who taught in the Department of University Studies before becoming director of the Center for Teaching Excellence a year ago. Professors often have to embrace the same uncertainty and risk they ask of their students. “The planning is time-intensive, there are lots of moving parts, and it might not even work,” she says. “You’re introducing new variables and opening yourself up to the class not going the way you thought it would. You have to be ready to bring the learning back around if something happens that you didn’t anticipate.”

In Jefferson’s experience, the St. Edward’s faculty is more than ready for the challenge. “We’re all mission-driven — that’s why we’re here,” she says. “We care about our students, and we want to help guide their experiences while they’re with us so that they’re informed about lots of different life paths they can take once they graduate.” To recognize professors who create those kinds of learning environments, the Center for Teaching Excellence annually bestows the Hudspeth Award for Innovative Instruction. A committee of faculty members from across disciplines and schools reviews and selects each year’s winner.

Creating experiential projects and activities that cultivate that kind of intense self-discovery isn’t easy. “You start by asking ‘Where do I want my students to be at the end of this? All right, how do I get there?’” says Jefferson, who taught in the Department of University Studies before becoming director of the Center for Teaching Excellence a year ago. Professors often have to embrace the same uncertainty and risk they ask of their students. “The planning is time-intensive, there are lots of moving parts, and it might not even work,” she says. “You’re introducing new variables and opening yourself up to the class not going the way you thought it would. You have to be ready to bring the learning back around if something happens that you didn’t anticipate.”

Hannah Cantu ’19, who took Drawing Methods with Robinson last year, was sitting in Molecular Genetics when she first started to see the connections Robinson tries to make semester after semester. As she looked at indigo-dyed cells under a microscope, “I thought about how much a hypothesis is like an art project,” says Cantu, who has studied water quality and macroinvertebrates in local watersheds while at St. Edward’s. “You can never fully predict what’s going to happen, and you have to look at things from new angles to be successful.”

The Environmental Science and Policy major decided to explore that idea in her final project for Robinson’s class — 20 themed drawings created in just 20 hours. Cantu chose garlic as her theme. “It seemed like the perfect symbol for what was going through my head. You can always go deeper and peel away another layer, whether it’s a molecular micro-process or a charcoal drawing.”

Cantu researched garlic cells and rendered them on paper; created abstractions of garlic cloves as taste buds; depicted the pungent smell in chaotic reds and bright yellows; and sketched the papery outer layers. By the end of the semester, “I had exhausted myself and my creativity,” but she understood that was exactly Robinson’s point: “Drawing had always been very straightforward for me,” she says. “In Alex’s class I came to realize that the creative process has less to do with art and more to do with instinct — what decisions do I make in the moment and why?”

Robinson’s in-class critiques after every project push students to answer those questions. “You quickly learn that there is no ‘correct’ with Alex. You leave class thinking, What does she want me to do? and you know she’s not going to tell you,” says Cantu. “But you can’t fully own your work until you make those decisions for yourself.”

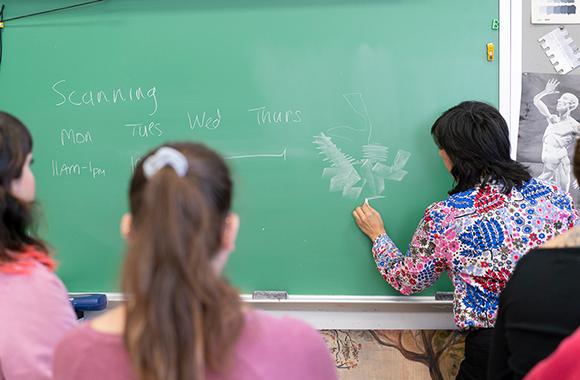

Last fall, Robinson’s Drawing Methods and Advanced Drawing courses — the latter of which enrolled two students — were combined into a single class period. Cantu took Advanced Drawing, while Nguyen and Charette were among the larger group in Drawing Methods. When Cantu showed up to class one day and saw the small pink bike, — bedazzled with daisies, streamers and a basket, kickstand-down in the center of the room — she knew exactly what was in store for the Drawing Methods students. She knew that Robinson didn’t just want the class to draw the tiny pink bike. She wanted them to draw it 10 times, filling the whole sheet each time and turning the paper 90 degrees every four minutes. Draw, time’s up, turn. Draw, time’s up, turn.

She remembered her own drawings from the year before: “My paper was a mess on a mess. It felt ruined from the start, so I couldn’t help but build ideas along the way to try to salvage something from it.” This time, as she worked on her advanced independent project, Cantu studied Nguyen and Charette as they studied the bike. She acutely remembered feeling the intrigued confusion that showed on their faces. But she also knew they would draw their way through it, just as she had.

“I really didn’t like that my drawings got to be so dark and overwhelming,” says Nguyen. “When we did the critique, Alex asked me why I felt that way and how I could change the feeling.” They talked about technique and intuition, how much mental weight to give each one, and how feeling in control (or out of it) could affect what showed up on the paper. “We really had to just draw without thinking, to draw what we saw, not what we knew,” says Nguyen. “It became all about letting our inspiration and ideas take over, and then we could go back and re-render our drawing using more conventional techniques.” In the end, Nguyen turned her 10 bikes into a garden, using color and collage to transform what she initially saw as “a dreary mess.”

Charette kept wondering, How did we start off drawing bikes, but end up with drawings that looked nothing like bikes? She decided to balance the overlapping dark marks with eraser marks, ending up with what looked to her like charcoal strands of hair. “I figured out that I had to look at my drawings in a more abstract way, and see not failure but creative opportunity.” She took that lesson with her to an internship at a music promotion company, where she makes videos to advertise upcoming shows. “Alex’s class has taught me that there’s value in failure,” she says. “Failing, or feeling like I failed, just means that I get to try again. I get to push myself to see the problem a different way the next time.”

Nguyen, too, has embraced the uncertainty. “Drawing is a pretty complicated process, and I’m learning that in the moment, or the series of moments, I can be really surprised by what I end up with,” she says. “I love the surprises that come from my brain.”

She calls it the “let-it-go technique,” and she recently added an Education minor so she can teach children to uncover and embrace what’s inside their own brains. “I realized when I was growing up in Vietnam that I didn’t want to waste the feeling I have when I draw — the concentration, the mental outlet. In Alex’s class, I’ve learned to trust that feeling and let it take my art wherever it wants to go,” she says. “It’s helped me in ways that have nothing to do with drawing,” like handling the culture shock that comes with speaking English all day, navigating Austin’s hilly roads and breakfast taco phenomenon, and grappling with Americans’ need for instant gratification.

Even though Robinson’s class is about making marks on paper, Cantu, Nguyen and Charette have learned just as much about how to make their mark in their world — local watersheds and campus labs, elementary classrooms, Austin’s design scene. That’s what they’ll carry with them after their sketchbooks are graded and slipped onto a shelf.

“Every project in Alex’s class seems to focus on two questions,” says Charette. “What does this mean to me? And where do I want to take it?”

It’s that questioning approach, that complexity, that deepens learning and makes the experience more meaningful for the students. And that can propel them anywhere.