The Digital Detective

Is it possible for others to know what apps have been used on a phone even after we’ve closed or deleted them from our devices? Do the sensors on our phones, from cameras to GPS, continue to reveal sensitive information, even when we don’t want them to?

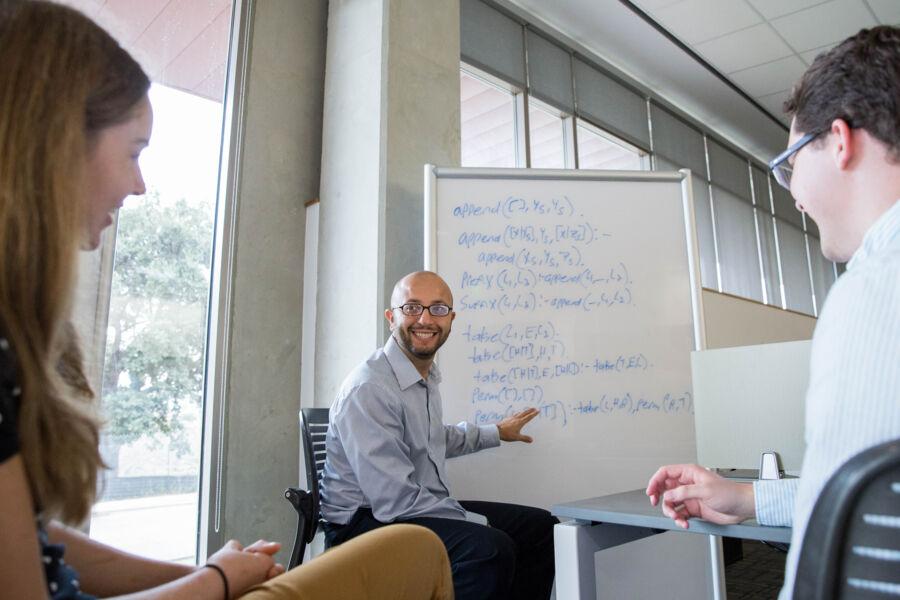

Students of Assistant Professor of Computer Science Bilal Shebaro are gaining insights into the who, what, when and how of digital security conundrums like these.

There’s no question that Shebaro’s expertise in computer security and digital forensics is extraordinarily valuable in our smartphone-addicted culture. His academic research focuses on specific kinds of “digital residue” that may give hackers and others a glimpse of our digital and physical whereabouts long after we believe we’ve cleared the information from our devices.

For Shebaro, tackling these mysteries is akin to finding and assembling the pieces of a highly complex puzzle. The same analytical thinking and problem-solving (and boundless curiosity) that he applies to his research is at the core of what he teaches his students — whether they’re delving into programming and operating systems or developing databases.

Here, he talks about his approach to teaching … and his digital forensics course.

How would you describe your teaching style?

I’m a big believer in learning by doing. Students remember the classes that are taught and practiced much better than just lectures on theory. So when I teach theory, we apply it to hands-on projects, almost always in the same class.

I also focus on tapping into each student’s interests. And there’s never a shortage of topics in this field that students are intrigued by or have ideas about. I have them pick their own project to work on ― something that really motivates them ― as long as it meets the course level and skills they need to learn.

Tell us about a favorite student project you’ve guided.

At the beginning of my Mobile Apps course, students are always saying to me, “Hey, I wish there was an app for this or for that.” I tell them that with the skills they learn in this class, they’ll have their app in hand and on their smartphone by the end of the course. It’s fascinating to see the different apps they come up with.

A popular project many students choose to work on is to develop a personal app about them. It could be a portfolio geared to potential employers that can act like a resume and display their projects. Or it might be an interactive blog about their special interests and activities, such as a diary with photos and videos of a trip they took. Personal websites have been around for quite a while, but personal apps are kind of a new thing, so students get excited about them. Some even make personal apps for other people.

How do you determine if a student project is successful?

Basically, there are three things I look for to ensure that students get the most out of their projects.

First, they have to provide a clear and convincing rationale and goal for their project. Why are they doing it? What’s the intended outcome? Why does it matter? Next, the work must challenge them to apply the theory and skills they are learning in the course. And third, their projects should tackle a real-world problem or need ― ideally for a good cause ― because that’s what they will encounter when they enter the industry. When these things come together, the results are always more tangible and meaningful to them.

What would you like students to know about your digital forensics course?

As we know from the news, movies and popular TV shows like CSI, digital evidence has become increasingly valuable to any criminal investigation. I teach an interdisciplinary course with the Forensic Sciences department that’s designed to bridge the gap between forensic science and digital forensics. It’s called Crime Scene in a Digital World, and it will prepare students with very timely and relevant skills in forensics. Students will learn how to handle digital investigations on electronic devices, from protocols for collecting forensic evidence at crime scenes to presenting digital evidence in court. It’s going to be an exciting class!