Crime Scenes Meet Virtual Reality

You’ve just walked into a hotel room. As you slowly scan the room, you notice an open suitcase by the door, a half-consumed bottle of beer on the desk, a container of pills by the television and … a dead body on the bed.

Crime Scene Investigations Class

This is the setting for a virtual crime scene in Associate Professor of Forensic Science Casie Parish Fisher’s Crime Scene Investigations class, where students use virtual reality (VR) goggles and investigate evidence that could be found at a real crime scene.

Parish Fisher uses two 360-degree cameras to shoot footage of mock crime scenes in real places; then she uploads photos and videos to a website that supports 360-degree conferencing. Students use both visual and audio cues to interact with and process the mock crime scene. As they move around the crime scene with VR goggles or on their computer, they can click on hotspots — bubbles of information that have embedded 360-degree photos, case information and instructions on how to proceed with the investigation.

“They often want to know what happened,” Parish Fisher says. “But I tell them all the time: It’s not your job to find out who did it. It’s your job to assess what you see, properly package it and preserve it, and get it to the laboratory for analysis.”

“I try to be very up front with my students as to what they can expect in the field,” she says. “I still do law enforcement training and interact with agencies all over the state to keep up with the changes that are happening. I want it to be as close to the real world as possible.”

She also makes sure her students know that what they see on television isn’t always an accurate representation of the real world. For one of their projects, students work as a group to analyze forensic-based shows like CSI and Bones. They find a quote or a scene that is either accurate or inaccurate, and they support their analysis using information from their practical crime-scene processing and investigation textbook.

Although the world has changed significantly in the last year, the pandemic precautions have reinforced what Parish Fisher was already teaching in her classes. “This is really not out of protocol for what we would be doing normally,” she says. “When you’re working a crime scene, you’re expected to wear a mask and use gloves for anything that you touch. I like for my students to get used to writing in gloves because when you’re on a scene, you have to take handwritten notes, and you have to write with gloves. The sooner your hands get accustomed to having those on, the better.”

VR Technology in the Classroom

Parish Fisher hasn’t seen the VR Technology being widely applied yet in the field, but its use in the classroom could soon become more widespread, and not just in her Crime Scene Investigations class. She’s already had discussions with other professors at St. Edward’s who have shown interest in using it in math courses to look at 3D shapes, or in mock trial courses so students could get a 360-degree look inside a courtroom. “At St. Ed’s, with teaching being at the forefront of what we do, I think we’re always trying to push the envelope and really be on the cutting edge, with our teaching styles and what we’re presenting in the classroom,” she says.

The students in the Crime Scene Investigations class move seamlessly between learning in the VR world and learning in person with patience, flexibility and an eagerness for more knowledge — all important qualities for a crime scene investigator. “They learn pretty quickly that it’s not glamorous work,” she says. “But if you love it, you’re hooked on it for life, and you love the thrill of going into work and never knowing what you’re going to see that day.”

“I try to be very up front with my students as to what they can expect in the field,” she says. “I still do law enforcement training and interact with agencies all over the state to keep up with the changes that are happening. I want it to be as close to the real world as possible.”

"Hands On" Crime Scene Investigation Experience

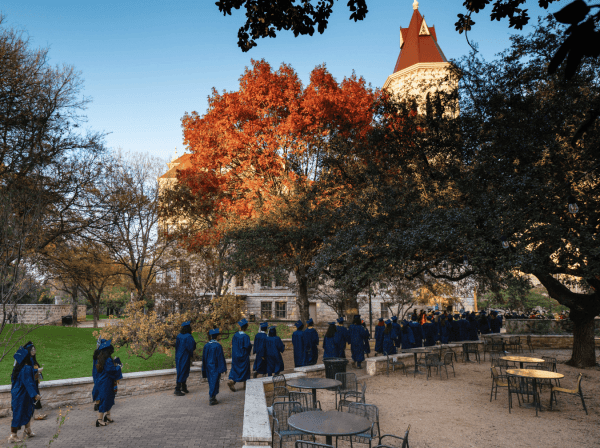

Students participating in a class and learning how to inspect a crime scene on campus